The Latest

Quick reads, small joys, and everyday moments from life on Nantucket.

Want to stay up to date on The Latest with Nancy? Join the newsletter!

Quick reads, small joys, and everyday moments from life on Nantucket.

Want to stay up to date on The Latest with Nancy? Join the newsletter!

Notes about island life, late-summer heat and backyard birds + a sneak peek at the “Hot Flash” book series and featured Holiday titles.

A quick recap of the summer as Nancy looks ahead to autumn and the holiday season. Don’t miss her short story “Magical Child” toward the end!

Family comes to visit Nancy this summer. They bring gifts and help with organizing the house! Link to The Hot Flash Club digital version on sale, too!

Summer is in full swing on Nantucket! To help you enjoy your time in the sun, here are some favorite books to check out.

Have you ever felt like you didn’t belong? My books are about the lives of “ordinary women” and most of us have experienced the sense…

In the summer of 1995, Ariel, Wyatt, Sheila and Nick come to Nantucket to work for the summer. They’ve just graduated from college and the…

Hello, everyone! I can’t stay away from themes involving sisters! Keely Green thinks of Isabelle Maxwell as her sister. They both live on Nantucket, they…

I just returned from my annual eye exam and nothing has changed, everything’s fine, so I came home and celebrated by enjoying four enormous truffles…

Yes, it’s still January, and here on Nantucket the temperature is 20 degrees! The weather is telling us to curl up on a couch or…

HAPPY NEW YEAR! I hope you all had a happy, busy holiday season. I love this time of year, when I can curl up with…

Hello, You Fabulous People! Yes, it is I, Dinah Lavender, author of over one hundred delicious romance novels, and here Iam, sharing all my secrets…

In my new novel, THE SUMMER WE STARTED OVER, Barrett Grant opens a shop on Nantucket. It’s named Nantucket Blues, and everything in her shop…

Pre-order The Summer We Started Over from Nantucket Book Partners and get an autographed copy, a blue notebook, and a Daffodil bookmark!

In Her Words presents thoughtful conversations with leaders across entertainment from film and television to media and gaming and everything in between; as we talk…

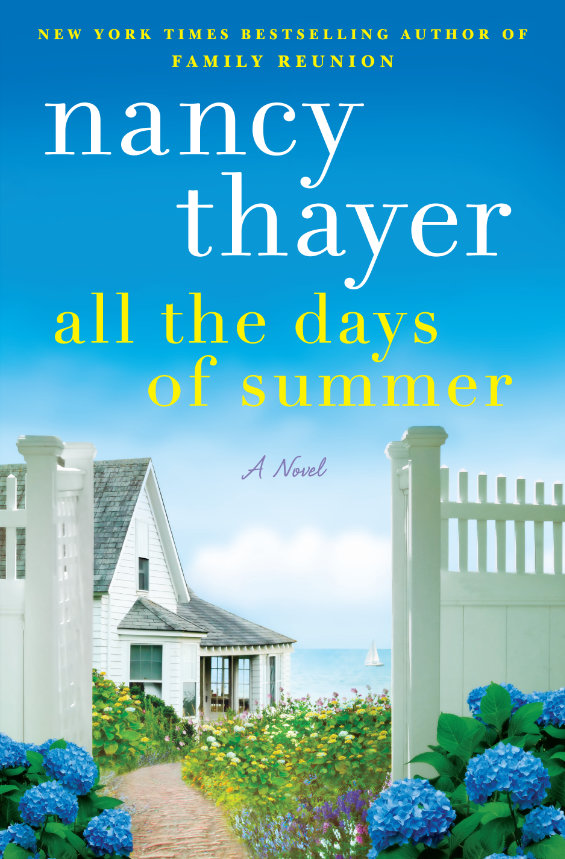

Enter for a chance to win! Keep all the lovely days of summer going into fall with a book club selection that will sweep you…

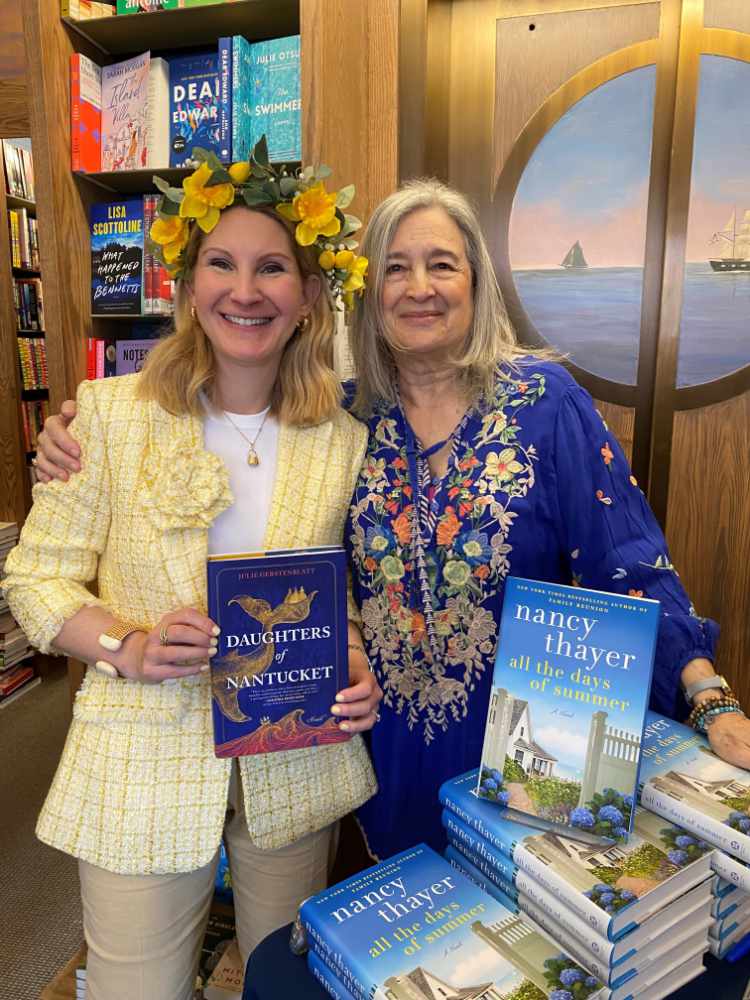

Tim Ehrenberg Reviews the book for N Magazine The release of a new Nancy Thayer novel is like the daffodils or cherry blossoms you’ll notice…

Hello everyone! Next Tuesday I’ll be launching my beautiful new website and I hope you check it out. Over the years, I’m met so many…

When Charley and I are asked what we’re doing for Thanksgiving and we tell them we’re staying home, just the two of us, people gasp…

Dear Readers, I keep telling myself it’s too early to think about Christmas gifts, but over the past week, I’ve found myself drifting helplessly to…

I hope you all had a great summer and read a lot of wonderful books! On Nantucket, we had a hot summer and no rain. It…

Step into Let it Snow with “Nantucket Noel” on the Hallmark Channel.

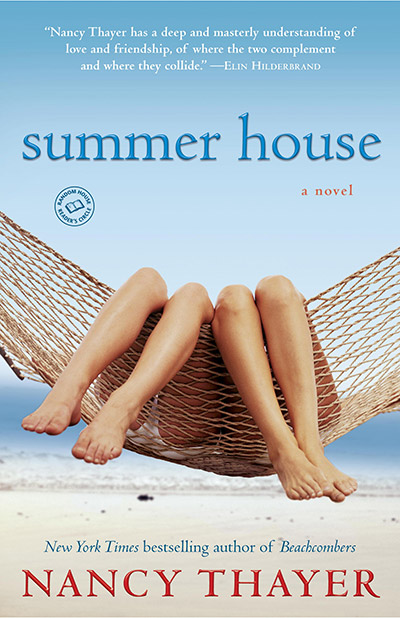

Some of my favorite people live in SUMMER HOUSE. Nona, the grandmother, is the best. She’s sweet but shrewd, loving but alert, and her history…

My novel Summer Breeze was inspired by the area around Lake Wyola in western Massachusetts. So many people I love live there. Plus, the mountains,…

Isn’t my new book beautiful? So many people help me with so many parts of it, and I thought you might like to meet some…

My mother Jane was super smart. She taught school and worked in the development office of a hospital. But she had the habit of getting…

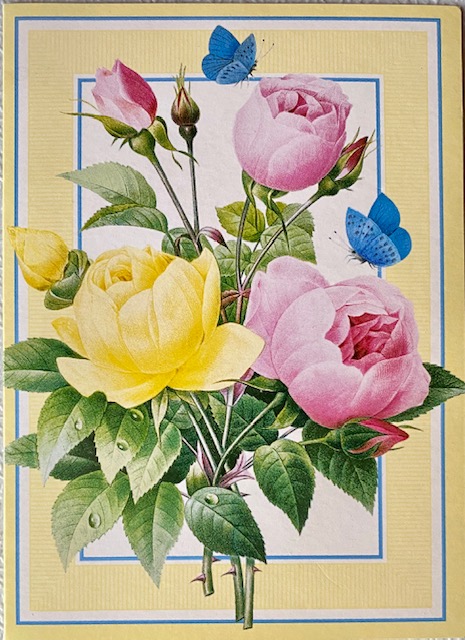

Bouquet of Tea Roses by Pierre-Joseph Redoute You might have guessed this, but I love flowers and the art made about them. I buy boxes…